A framework leveraging SSL & AL, to perform Classification via drone yield images.

Take a look at FRDC: Forest Recovery Digital Companion for a no-math high level overview.

Introduction

Monitoring forestry health via unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) is a rather niche field in Machine Learning. Due to that, not much advancements have been made in this front. However, in other fronts, such as state-of-the-art generic Image Classification models, Semi-Supervised learning frameworks, Active Learning strategies, they have all been moving forward at a rapid pace. These are all essential components to make FRDC work, and thankfully, we can easily leverage these knowledge in FRDC.

FRDC

Forest Recovery Digital Companion (FRDC) is an entire full-stack application that leverages machine learning to perform forestry health monitoring. In particular, for this first part, we’ll focus on simply Tree Species classification, and in the future, we’ll delve into more metrics such as tracking the carbon density, tree health, diversity and much more.

Background

Before we dive into FRDC, we should talk more on the mathematical justification, it’s going to be math heavy, however it’s distilled knowledge.

Is 50 samples enough for ML?

At the start of FRDC, we had a very peculiar problem. We don’t have much data, and getting more is not only costly, but also legally difficult. See, Singapore is uptight on security (for good reasons), therefore flying drones at will around Singapore will not fly (pun intended). This problem was exacerbated by the fact that labelling these tree species is not easy either. These forests are so dense that tree canopies (the top of the trees) tend to overlap each other. We found that in many instances, what the ecologists (our human annotators) see on the ground may not match up with the coordinates on top.

Due to the above, we only managed to yield around 50 samples, across 2 time-stamps. Wouldn’t it be interesting, if we can train a ML model with just that?

What’s wrong with training with too little samples?

Before we jump into the assumption that little data = bad model, we should justify why is that the case?

Going down to the lowest-level of ML, we’re finding a model $f$, out of all possible models $\mathcal F$. Such that this model can transform all inputs $\mathcal X$ into targets $\mathcal Y$ with minimal error $\ell$. We denote this metric to minimize as $R$, the risk.

\[R(f) = \int\ell(f(x),y)dP(X,Y)\]The above formula integrates across the probability surface $P(X,Y)$, which says that: If the loss $\ell$ is weighed by the probability of that loss. However, practically, $P(X,Y)$ is unknown, much like population statistics, and can only be estimated by samples.

If we have samples ${(x_1, y_1), …, (x_n, y_n)}$, and $\delta$ as dirac delta. A simple estimation is to simply assume that the true probability surface is the same as the sampled probability space. This approach is know as Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM)

\[\begin{align*} P(X,Y)&\approx P_\delta(X,Y)=\frac1n\sum_{i=1}^n\delta(x_i, y_i)\\ \therefore R(f)&=\sum_{i=1}^n\ell(f(x_i), y_i), f_{best}=\arg\min_{f}R(f) \end{align*}\]However, finding this model $f$ is actually trivial, it just needs to memorize all of the input data, much like a hashmap (thus Empirical). This means that $\ell$ will always be $0$, a perfect model!

However, if we throw in an input it hasn’t seen before, it’ll likely break, this is because it never learnt to generalize.

Predicting Unseen Samples

So, in order for the model to predict anything it hasn’t seen before, it needs to somehow infer information from nearby seen samples. The key issue in estimating with $P_\delta(X,Y)$ is that $\delta$ only encodes the point estimate of $X$. This means that for any $\hat X\not\in X$, the probability is undefined.

To solve this, we need to include unseen samples within the training dataset. But how do we even provide a sample we haven’t seen before?

The answer is to artificially construct samples that are close to the original sample. This allows the model to learn a more holistic perspective on the data, over just a single point. Which leads us to Vicinity Risk Minimization (VRM), proposing a new probability surface:

\[P(X,Y) \approx P_v(\tilde x, \tilde y)=\frac1n\sum_{i=1}^n v(\tilde x, \tilde y|x_i, y_i)\]In simpler terms, the new probability surface is constructed by these new artificial samples, that are sampled from this $v$ function. So for a single seen sample, we can generate an infinite number of artificial samples in the vicinity, resulting in a much smoother probability surface.

As a result, points not seen before can now “infer” from nearby seen samples!

An example of a vicinity function is the normal distribution $v(\tilde x, \tilde y|x_i, y_i) = \mathcal N(\tilde x -x_i,\sigma^2)\delta(y=y_i)$. Artificial samples will be constructed by randomly applying additive Gaussian noise to the original input.

To apply this VRM strategy to the field of Image Classification, we commonly use Image Augmentation techniques, described below.

Augmentation

Despite VRM being logically sound, its major caveat is that $v(\tilde x, \tilde y|x_i, y_i)$ needs to be defined, and “vicinity” functions of an image is non-trivial due to high-dimensionality.

Recall that the purpose of VRM, is to find samples that are within its vicinity, that will highly likely be associated with the same target. To give an example, if we took an image of a cat, flip it horizontally, it’s still a cat. This fits the purpose of VRM, while not exactly mathematically, it’s essentially what we’re achieving. These set of VRMs are more commonly known as Image Augmentations.

There are many more:

- Rotation Augmentation

- Color Augmentation

- Scale Augmentation

- Random Crop Augmentation

- …

These functions act as a way to transform $x$ into something else, but because it’s the same image, conveying the same information (a cat), the model output must be the same! This is the exact definition of Consistency Regularization.

Consistency Regularization

If an image $x$ is perturbed (augmented) realistically as $\hat x$, such that it’s highly possible to yield that perturbed image sample in real life, the model should predict the same prediction for both $x$ and $\hat x$.

We can define the target to minimize:

\[||f(\text{Aug}(x))-f(\text{Aug}(x))||^2_2\]As $f$ and $\text{Aug}$ may be stochastic, this optimization problem not necessarily trivial!

Augmentation techniques are not necessarily equal:

- Stronger Augmentations yield a further offset from the original sample, i.e. VRM with high variance. e.g. Colour Shifts/Random Crops/CutOut

- Weak Augmentations yield smaller offsets, i.e. VRM with small variance. e.g. Horizontal Flip (in most contexts), Center Crop.

In another perspective, we can consider that Weak Augmentations are more likely to be sampled from the true dataset, while Strong Augmentations, due to lower quality and highly noisy captures, is less likely.

Thus it’s not reasonable to zero out Consistency Irregularity, but minimizing guides the model to a more holistic perspective of the data space.

mixup

mixupis authored as lowercase

A more generic, simple, yet groundbreaking augmentation strategy is to sample a random point between 2 data points, then modify the target, based on their relative distances between each point. An example is due:

Take for example:

You sample a pair of input data $x_1=(5, 10), x_2=(15,30)$ Corresponding to a known one-hot labels $y_1=(1,0), y_2=(0,1)$

Then, sample a mixing factor $\lambda$, randomly (the paper suggests a Beta Distribution) between $[0,1]$. Let’s say $\lambda=0.5$, which means to take the midpoints of $x$ and $y$. Then your new sample is $x_{mix}=(10,20), y_{mix}=(0.5,0.5)$, which is a linear interpolation between the 2 points.

The authors of mixup argued that this augmentation technique is a good VRM technique that involves pair-wise points, furthermore, due to its simplicity of linear interpolation, it’s a good reflection of Occam’s Razor.

In images, the concept carries across, if you have 2 images, simply blend them together by a certain factor $\lambda$, and also its label. What’s it really doing though?

mixup is essentially assuming that between all samples, there exists a sample that lies within the samples. Think of a Convex Hull that “wraps” all samples in this input space, mixup is effectively allowing the model to learn anything within this convex set.

There is an important caveat though, when we transform raw images in the input space, it arguably produces unrealistic images, but then again, the label, being partially each class, may not make sense either. I believe there’s much needed justification, despite success of this augmentation approach.

Wait, so is 50 enough?

After all of that, we can start to understand, that we don’t just have 50 samples, instead, a 50 reference points to generate samples from. This is what made our approach successful despite so little samples from each class.

We have a 1000 unlabeled ones, does that help?

Closing off with the concept of Supervised Learning above, which is to train with labeled data, we now move on to discussing how unlabeled data can help inform models.

Point Density and Decision Boundaries

Again, before jump into the conclusion, let’s take a step back and evaluate our fundamentals.

For a dataset $\mathcal X$, after feature extraction, will exist in some manifold within a feature space $\Omega$. Then there exists regions where points are dense, and those sparse.

Logically:

- dense regions are indicative of “clusters”, which usually means that they are likely to be from a single class.

- then, sparse regions are indicative of “cluster boundaries”, where cluster regions meet.

In discrimitive classification models, the goal is to construct boundaries that slice through lowest density regions, that best separates clusters. So what’s the problem with just labeled data?

Why we need unlabeled data

In the simplest case, let’s consider this:

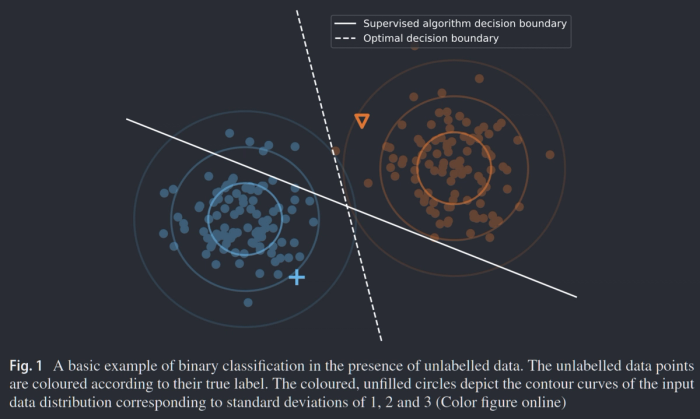

Source: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-019-05855-6 A survey on semi-supervised learning Jesper E. van Engelen 1 · Holger H. Hoos

The above shows 2 clusters, where the circles $\bigcirc$ represent unlabeled points, while we have $+$ and $\nabla$ labeled.

Given that we only use the labeled data, we’d find that the learnt decision boundary will just be halfway between them. This is not great as it slices through high-density regions of the actual clusters. However, to fix that, we need to know the labels all of these other unlabeled points, so how do we do that?

Smoothness Assumption

Through visual inspection, even if we didn’t label most $\bigcirc$ points, we can see that there are 2 clusters, and we can specify a decision boundary. This is because those points are spatially clustered together in 2 big chunks, therefore we infer 2 classes.

The above evaluation follows the Smoothness Assumption of Semi-Supervised Learning:

Points close together are likely to come from the same class.

It’s “smoothness” can be also thought of from the perspective of a decision boundary: If 2 points were close together (in a cluster), yet they are from * *different classes, that requires an **extremely sharp decision boundary. We assume that the above doesn’t happen (often).

Pseudo-Labelling

To summarize:

- Points close together form a cluster

- Labeled points come from one of the above clusters

Assuming our assumption holds, we can iteratively label unlabeled data, starting with the most confident ones near labeled points. These will receive “pseudo-labels” to guide further labeling. As hinted, the points closest to the labeled points are most likely to be the same class as those points.

The most basic SSL architectures propose the following steps:

- Train model on labeled points

- Assign pseudo-labels to the most confident points, leave uncertain points untouched

- Repeat Step 1 & 2 until satisfied

- Test on new dataset

However, that’s not the end, there’s more improvements to this.

Confirmation Bias

By simply applying the above algorithm, an expected concern surfaces:

Overfitting to incorrect pseudo-labels predicted by the network is known as confirmation bias. It is natural to think that reducing the confidence of the network on its predictions might alleviate this problem and improve generalization.

It’s fair to assume that the model will eventually makes errors even if the confidence is high. By using hard pseudo-labels (one-hot encoded labels), the model is penalized heavily for uncertain predictions on any hard pseudo-labels. As there’s no distinction between labels and pseudo-labels, the model is forced to propagate errors from previous model iterations.

There are a few solutions to this, however, it all relies on soft pseudo-labels, where an unlabeled point is assigned a distribution instead of a one-hot label.

[…] soft-labels contain the probabilities of each class in themselves. Soft-labels reflect confidences of the trained network unlike hard-labels, which are assigned by ignoring confidences.

As expected, in contrast with hard-labels, the model will be penalized less with uncertain predictions on uncertain pseudo-labels, giving more freedom for models to accept ambiguous data.

In conjunction with methods that introduces input or feature-space perturbations such as image augmentations or mixup, the model will be more robust against bad predictions.

Unlabeled Augmentations

Much like our justifications on our labeled data, we can utilize augmentations on our unlabeled data to generate alternative points. This technique simply multiplies the number of unlabeled points, helping generalization of our decision boundaries

However, because we don’t have labels, it’s usually important to constraint augmentations of the same unlabeled data point to the same class. Stronger augmentations can possibly augment images such that they end up in another cluster.

One must be aware of how some augmentations can possibly make a data point “ change” class. For example, color & size augmentations changing a “red apple” to “green grapes”. This principle doesn’t just apply to unlabeled data.

Low-Density Decision Boundary Assumption: Entropy Minimization

On top of the smoothness assumption, another is that decision boundaries should optimally cut through low-density areas. By default, this should have been checked off, but we can further encourage the models to favor those decision boundaries that yield higher confidence samples.

Entropy is the measurement of “uncertainty” for predictions. A simple example is that

- a fair-coin has maximum entropy, because we cannot predict the outcome at all.

- while a double-headed coin has minimum entropy, because we always know the outcome.

In the context of ML, with discriminative frameworks, points that are far away from decision boundaries always yields low entropy. In other words, the model has low uncertainty that this point is labeled correctly. Conversely, points near boundaries will have high entropy, as the model has the highest uncertainty.

The motivation is to encourage the models to produce low-entropy predictions, more confident ones. To achieve this, the decision boundaries are encouraged to be sharper between clusters

This may seem contradictory to the smoothness assumption. Entropy minimization sharpens decision boundaries between clusters. Smoothness Assumption assumes all points in a cluster are of the same class. They are mutually exclusive, but are logically necessary to simplify the task.

As such, the method of making the boundaries steeper is also known as “ Sharpening”.

The formula used in MixMatch

\[\text{Sharpen}(p,T)_i := p_i^{1/T}\bigg/\sum_{j=1}^Jp_j^{1/T}\]This simply boosts the most confident prediction, while suppresses the rest.

Novelty Detection

In many ML applications, not only is the accuracy of classification important, but also knowing when a sample doesn’t even belong in the classes we know. For example, given that we are classifying trees, having the model reject or flag out samples that aren’t even trees is a much better result than erronously classifying it as the “nearest” look-alike tree. These samples can be thought of as out-of-distribution (OOD). Specifically, this task is known as “Multi-class Novelty Detection”